There is a long history of anti-malaria activities in Australia. Malaria was endemic in the northern, tropical areas and there were various outbreaks in Darwin and Far North Queensland in the early years of recording.

Malaria became of major concern during the years of the second World War, when large numbers of troops were circulating through the northern parts of Australia and other more malarious areas in PNG, the Pacific and South East Asia. The movement of defence personnel and the risks from them importing malaria, have remained and the military involvement in malaria control and research continues with the Australian Defence Force Malaria and Infectious Diseases Institute (previously the Australian Army Malaria Institute). There are also several high-level medical institutes with involvement in malaria research. The vivax malaria research team at the Walter and Eliza Hall Institute won the 2019 Eureka prize for infectious diseases research.

Australia’s profile in malaria control was raised when Melbourne hosted the 1st Malaria World Congress in 2018 and Australia is active in APLMA (Asia Pacific Leaders Malaria Alliance, an affiliation of Asian and Pacific heads of government formed to accelerate progress against malaria and to eliminate it in the region by 2030).

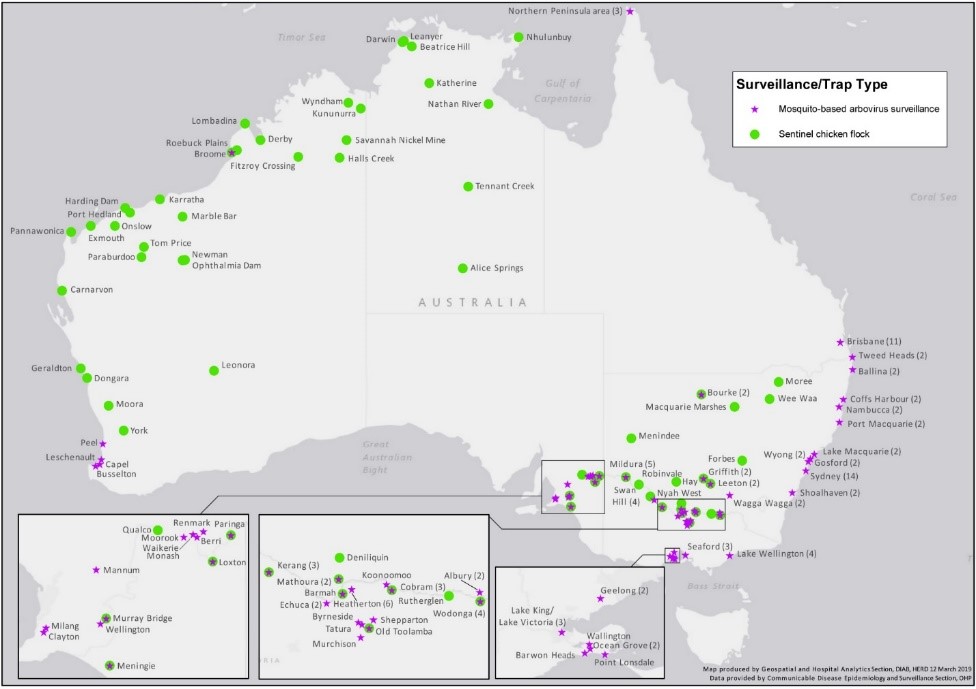

Malaria reporting in Australia comes under the National Notifiable Diseases Surveillance System. The surveillance system involves reporting of human illnesses by medical staff; sentinel chicken flocks; and vector and virus surveillance programs – activities such as surveillance for exotic mosquitos at ports of entry eg at international airports. In 2014-15, there were 36 separate detections of exotic mosquitoes, including one albopictus larva in water that was pooling inside a new tyre being imported from Japan (Knope 2019: 51).

For the latest reported year – 2014-2015 – there were 12,489 cases of mosquito borne diseases in Australia, mostly Barmah Forest and Ross River viruses. There were 259 cases of malaria, all acquired overseas. The report states that the last cases acquired on mainland Australia were during an outbreak in north Queensland in 2002; and that limited transmission occurs occasionally in the Torres Strait. (Knope 2019: 26) An example of this is described in a 2011 article from the Torres News Online, 8 Apr 2011.

Rogue mozzie spreads malaria

JUST one rogue mosquito could be responsible for the closure of the sea border between Papua New Guinea and Australia. Border restrictions between the two countries were put in place on Monday, March 28, following a malaria outbreak in the Torres Strait Islands. Queensland Health and the Torres Island Regional Council say they are taking the threat “very seriously” after four residents of the Outer Islands contracted the more-severe form of the disease last week.

A spokesperson from Queensland Health said “We could be talking about one rogue mosquito, that has bitten an infected person before transferring it to the others. The disease was acquired locally, possibly from someone travelling down from PNG. The disease is not usually present in Far North Queensland, and needs to be imported from malarial countries before local transmission can occur.”

On 28 March the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade put a restriction on inward visits from PNG to Boigu, Dauan and Saibai. The restrictions, which expired on April 11, applied to the traditional movements of citizens of PNG who live in the adjacent coastal area of Papua New Guinea to the Torres Strait Protected Zone.

Far North Queensland is a malaria-receptive zone, which means the Anopheles mosquito can transfer the disease if the malaria parasite is present in the area. Queensland Health deployed mosquito control staff, public health nurses and public education staff to help reduce the risk of further cases, spraying homes with a residual insecticide, setting mosquito traps, and fogging at dusk to kill as many mosquitoes as possible. Wearing insect repellent, especially if outside during dusk or at night, when the malaria mosquito bites, mosquito bed nets, mosquito coils, and plug-in mosquito repellent devices are also recommended.

Unlike the dengue mosquito, which is a day-biter, the Anopheles malaria mosquito bites mainly in the evening and at night. While the dengue mosquito breeds in containers around the home, the malaria mozzie breeds in surface water such as swamps and lagoons. Records going back to 1997 indicate that there have been no known deaths from malaria in the Torres Strait

The Australian Defence Forces serving overseas continue to contract both falciparum and vivax malaria. For example, in the ten years 1998-2007, a total of 487 soldiers in Timor Leste, Bougainville, and the Solomon Islands were infected, with many of the cases (recurrent vivax) being discovered after return to Australia.

As with “elimination” everywhere, a constant vigilance of testing, reporting and treating is needed to prevent recurrence of malaria.

Jen Parer

RC Holbrook

RAM supervisor D9790

Elmes, Nathan J. 2010 Malaria Notifications in the Australian Defence Force from 1998 to 2007. International Health vol. 2 https://www.defence.gov.au/health/healthportal/malaria/Documents/Malaria%20notifications%20in%20the%20ADF%201998-2007.pdf [accessed 4/07/20]

Knope, K et al 2019 Arboviral diseases and malaria in Australia, 2014–15: Annual report of the National Arbovirus and Malaria Advisory Committee. Communicable Diseases Intelligence vol. 43 https://www1.health.gov.au/internet/main/publishing.nsf/Content/75F30C0D2C126CAECA2583940015EDE3/$File/arboviral_diseases_and_malaria_in_Australia-_NTAC_2014%E2%80%9315_annual_report.pdf [accessed 2/07/2020]